The following are notes from the book: The Intelligent Investor by Ben Graham. Graham was a professor at Columbia, who set forth and popularized the idea of “value investing”. Value investing is about determining the intrinsic value of an investment and buying when the price is markedly below the actual value that investment. The primary factor for profit does not come from the actual growth or success of the investment but from identifying when the actual purchase is mispriced. This is akin to buying items cheaply from a garage sale and selling it for much higher prices on e-bay. Unlike growth investing, which depends on the company growing far beyond what is currently expected or momentum investing which has to do with getting timing right on the market, Graham explains his investment style along the lines of methodical reasoning and sobering calculations.

Notes from The Intelligent Investor:

-To enjoy a reasonable chance for continued better than average results, the investor must follow policies which are (1) inherently sound and promising, and (2) not popular on Wall Street.

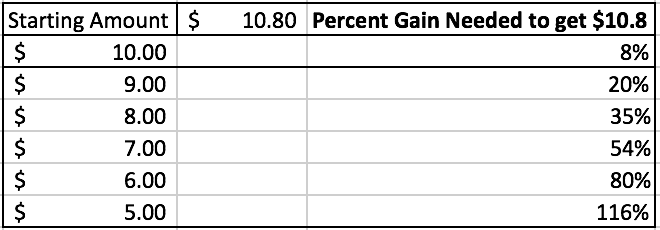

-don’t lose money. Its harder to make the money back once you’ve lost money.

Investing, according to Graham, consists equally of three elements:

• you must thoroughly analyze a company, and the soundness of its underlying businesses, before you buy its stock;

• you must deliberately protect yourself against serious losses;

• you must aspire to “adequate,” not extraordinary, performance.

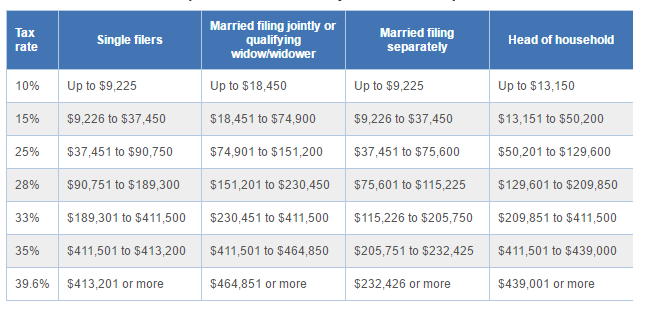

-two inflation fighters: REITs and TIPS (TIPS paper gain is taxable income, better in tax-exempt account)

-the intelligent investor must never forecast the future exclusively by extrapolating the past.

-The value of any investment is, and always must be, a function of the price you pay for it.

-the corollary to that law of financial history is that the markets will most brutally surprise the very people who are most certain that their views about the future are right.

-By the rule of opposites,” the more enthusiastic investors become about the stock market in the long run, the more certain they are to be proved wrong in the short run.

-technical trading would not merit buying a stock when it falls but if the value of the investment is assured when you buy it, then buying when a stock drops would make sense. Otherwise, if youre in a pure technical trading environment such as crypto, you’re better off following those principles

In these cases the market has sufficient skepticism as to the continuation of the unusually high profits to value them con- servatively, and conversely when earnings are low or nonexistent. (Note that, by the arithmetic, if a company earns “next to nothing”

The better the quality of a common stock, the more speculative it is likely to be

investing isn’t about beating oth- ers at their game. It’s about controlling yourself at your own game.

In our own experience we have noted among them (financial analysts) a pervasive attitude which we think tends to impair what could otherwise be more useful advisory work. This is their general view that a stock should be bought if the near-term prospects of the business are favorable and should be sold if these are unfavorable—regardless of the current price.

We suggest that analysts work out first what we call the “past-performance value,” which is based solely on the past record. This would indicate what the stock would be worth. The second part of the analysis should consider to what extent the value based solely on past performance should be modified because of new conditions expected in the future.

Which factors determine how much you should be willing to pay for a stock? What makes one company worth 10 times earnings and another worth 20 times? How can you be reasonably sure that you are not overpaying for an apparently rosy future that turns out to be a murky nightmare?

Graham feels that five elements are decisive.1 He summarizes them as:

• the company’s “general long-term prospects”

• the quality of its management

• its financial strength and capital structure

• its dividend record

• and its current dividend rate.

Let’s look at these factors in the light of today’s market.

The long-term prospects. Nowadays, the intelligent investor should begin by downloading at least five years’ worth of annual reports (Form 10-K) from the company’s website. Get one year of quarterly reports too

Then comb through the financial state- ments, gathering evidence to help you answer two overriding ques- tions. What makes this company grow? Where do (and where will) its profits come from? Among the problems to watch for:

• The company is a “serial acquirer.” An average of more than two or three acquisitions a year is a sign of potential trouble. After all, if the company itself would rather buy the stock of other busi- nesses than invest in its own, shouldn’t you take the hint and look elsewhere too? And check the company’s track record as an acquirer. Watch out for corporate bulimics—firms that wolf down big acquisitions, only to end up vomiting them back out. Lucent, Mattel, Quaker Oats, and Tyco International are among the com- panies that have had to disgorge acquisitions at sickening losses. Other firms take chronic write-offs, or accounting charges proving that they overpaid for their past acquisitions. That’s a bad omen for future deal making.

• The company is an OPM addict, borrowing debt or selling stock to raise boatloads of Other People’s Money. These fat infusions of OPM are labeled “cash from financing activities” on the statement of cash flows in the annual report. They can make a sick company appear to be growing even if its underlying businesses are not generating enough cash—as Global Crossing and WorldCom showed not long ago.

you study the sources of growth and profit, stay on the lookout for positives as well as negatives. Among the good signs:

• The company has a wide “moat,” or competitive advantage. Like castles, some companies can easily be stormed by marauding competitors, while others are almost impregnable. Several forces can widen a company’s moat: a strong brand identity (think of Harley Davidson, whose buyers tattoo the company’s logo onto their bodies); a monopoly or near-monopoly on the market; economies of scale, or the ability to supply huge amounts of goods or services cheaply (consider Gillette, which churns out razor blades by the billion); a unique intangible asset (think of Coca- Cola, whose secret formula for flavored syrup has no real physical value but maintains a priceless hold on consumers); a resistance to substitution (most businesses have no alternative to electricity, so utility companies are unlikely to be supplanted any time soon).5

The company is a marathoner, not a sprinter. By looking back at the income statements, you can see whether revenues and net earnings have grown smoothly and steadily over the previous 10 years. A recent article in the Financial Analysts Journal confirmed what other studies (and the sad experience of many investors) have shown: that the fastest-growing companies tend to overheat and flame out.6 If earnings are growing at a long-term rate of 10% pretax (or 6% to 7% after-tax), that may be sustainable. But the 15% growth hurdle that many companies set for themselves is delusional. And an even higher rate—or a sudden burst of growth in one or two years—is all but certain to fade, just like an inexperi- enced marathoner who tries to run the whole race as if it were a 100-meter dash.

• The company sows and reaps. No matter how good its products or how powerful its brands, a company must spend some money to develop new business. While research and development spending is not a source of growth today, it may well be tomor- row—particularly if a firm has a proven record of rejuvenating its businesses with new ideas and equipment. The average budget for research and development varies across industries and com- panies. In 2002, Procter & Gamble spent about 4% of its net sales on R & D, while 3M spent 6.5% and Johnson & Johnson 10.9%. In the long run, a company that spends nothing on R & D is at least as vulnerable as one that spends too much.

The quality and conduct of management. A company’s execu- tives should say what they will do, then do what they said. Read the past annual reports to see what forecasts the managers made and if they fulfilled them or fell short. Managers should forthrightly admit their failures and take responsibility for them, rather than blaming all-purpose scapegoats like “the economy,” “uncertainty,” or “weak demand.” Check whether the tone and substance of the chairman’s letter stay constant, or fluctuate with the latest fads on Wall Street. (Pay special attention to boom years like 1999: Did the executives of a cement or underwear company suddenly declare that they were “on the leading edge of the transformative software revolution

To fine-tune the definition of owner earnings, you should also subtract from reported net income:

•any costs of granting stock options, which divert earnings away from existing shareholders into the hands of new inside owners

-any “unusual,” “nonrecurring,” or “extraordinary” charges

-any “income” from the company’s pension fund.

Next, look at the company’s capital structure. Turn to the balance sheet to see how much debt (including preferred stock) the company has; in general, long-term debt should be under 50% of total capital. In the footnotes to the financial statements, determine whether the long-term debt is fixed-rate (with constant interest payments) or vari- able (with payments that fluctuate, which could become costly if inter- est rates rise).

In our opinion, the proper mode of calculation would be first to consider the indicated earning power on the basis of full income- tax liability, and to derive some broad idea of the stock’s value based on that estimate. To this should be added some bonus figure, representing the value per share of the important but temporary tax exemption the company will enjoy. (Allowance must be made, also, for a possible large-scale dilution in this case.

In short, pro forma earnings enable companies to show how well they might have done if they hadn’t done as badly as they did.2 As an intelligent investor, the only thing you should do with pro forma earn- ings is ignore them.

A few pointers will help you avoid buying a stock that turns out to be an accounting time bomb:

Read backwards. When you research a company’s financial reports, start reading on the last page and slowly work your way toward the front. Anything that the company doesn’t want you to find is buried in the back—which is precisely why you should look there first.

Read the notes. Never buy a stock without reading the footnotes to the financial statements in the annual report. Usually labeled “sum- mary of significant accounting policies,” one key note describes how the company recognizes revenue, records inventories, treats install- ment or contract sales, expenses its marketing costs, and accounts for the other major aspects of its business.7 In the other footnotes, watch for disclosures about debt, stock options, loans to customers, reserves against losses, and other “risk factors” that can take a big chomp out of earnings.

By contrast, those who emphasize protection are always espe- cially concerned with the price of the issue at the time of study. Their main effort is to assure themselves of a substantial margin of indicated present value above the market price—which margin could absorb unfavorable developments in the future.

Keeping your money spread across many stocks and industries is the only reliable insurance against the risk of being wrong.

But if it is true that a fairly large segment of the stock mar- ket is often discriminated against or entirely neglected in the stan- dard analytical selections, then the intelligent investor may be in a position to profit from the resultant undervaluations.

But to do so he must follow specific methods that are not gener- ally accepted on Wall Street, since those that are so accepted do not seem to produce the results everyone would like to achieve. It would be rather strange if—with all the brains at work profession- ally in the stock market—there could be approaches which are both sound and relatively unpopular. Yet our own career and reputation have been based on this unlikely fact.

Mason Value Trust like to see rising returns on invested capital, or ROIC—a way of measuring how efficiently a company generates what Warren Buffett has called “owner earnings.”

Finally, most leading professional investors want to see that a com- pany is run by people who, in the words of Oakmark’s William Nygren, “think like owners, not just managers.” Two simple tests: Are the company’s financial statements easily understandable, or are they full of obfuscation? Are “nonrecurring” or “extraordinary” or “unusual” charges just that, or do they have a nasty habit of recurring?

Longleaf’s Mason Hawkins looks for corporate managers who are “good partners”—meaning that they communicate candidly about problems, have clear plans for allocating current and future cash flow, and own sizable stakes in the company’s stock (preferably through cash purchases rather than through grants of options). But “if man- agements talk more about the stock price than about the business,” warns Robert Torray of the Torray Fund, “we’re not interested.” Christopher Davis of the Davis Funds favors firms that limit issuance of stock options to roughly 3% of shares outstanding.

Robert Rodriguez of FPA Capital Fund turns to the back page of the company’s annual report, where the heads of its operating divi- sions are listed. If there’s a lot of turnover in those names in the first one or two years of a new CEO’s regime, that’s probably a good sign; he’s cleaning out the dead wood. But if high turnover continues, the turnaround has probably devolved into turmoil.

No matter which techniques they use in picking stocks, successful investing professionals have two things in common: First, they are dis- ciplined and consistent, refusing to change their approach even when it is unfashionable. Second, they think a great deal about what they do and how to do it, but they pay very little attention to what the market is doing.

Observation over many years has taught us that the chief losses to investors come from the purchase of low-quality securities at times of favorable business conditions. The purchasers view the current good earnings as equivalent to “earning power” and assume that prosperity is synonymous with safety. It is in those years that bonds and preferred stocks of infe- rior grade can be sold to the public at a price around par, because they carry a little higher income return or a deceptively attractive conversion privilege. It is then, also, that common stocks of obscure companies can be floated at prices far above the tangible investment, on the strength of two or three years of excellent growth.

In investment theory there is no reason why carefully estimated future earnings should be a less reliable guide than the bare record of the past; in fact, security analysis is coming more and more to prefer a competently executed evaluation of the future. Thus the growth-stock approach may supply as dependable a margin of safety as is found in the ordinary investment— provided the calculation of the future is conservatively made, and provided it shows a satisfactory margin in relation to the price paid.

Graham is saying that there is no such thing as a good or bad stock; there are only cheap stocks and expensive stocks. Even the best company becomes a “sell” when its stock price goes too high, while the worst com- pany is worth buying if its stock goes low enough

For the enterprising investor this means that his operations for profit should be based not on optimism but on arithmetic. For every investor it means that when he limits his return to a small figure—as formerly, at least, in a conventional bond or preferred stock—he must demand convincing evidence that he is not risking a substantial part of his principal.

Have the courage of your knowledge and experience. If you have formed a conclusion from the facts and if you know your judgment is sound, act on it— even though others may hesitate or differ.” (You are neither right nor wrong because the crowd disagrees with you. You are right because your data and reasoning are right.) Similarly, in the world of securities, courage becomes the supreme virtue after adequate knowledge and a tested judgment are at hand.

Imagine that you find a stock that you think can grow at 10% a year even if the market only grows 5% annually. Unfortunately, you are so enthusiastic that you pay too high a price, and the stock loses 50% of its value the first year. Even if the stock then generates double the market’s return, it will take you more than 16 years to overtake the market—simply because you paid too much, and lost too much, at the outset.

The Nobel-prize–winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman explains two factors that characterize good decisions:

• “well-calibrated confidence” (do I understand this investment as well as I think I do?)

• “correctly-anticipated regret” (how will I react if my analysis turns out to be wrong?).

Before you invest, you must ensure that you have realistically assessed your probability of being right and how you will react to the consequences of being wrong.

In the context of investing, leverage means using additional money that’s taken out as a loan to invest into a product that is expected to produce higher returns. If someone takes a bank loan of 4% interest to create a coffee shop that can produce 20% return within the year, they will have made successful use of leverage.

In the context of investing, leverage means using additional money that’s taken out as a loan to invest into a product that is expected to produce higher returns. If someone takes a bank loan of 4% interest to create a coffee shop that can produce 20% return within the year, they will have made successful use of leverage.